Cranial Cruciate Ligament Rupture In Rottweilers

By Dr. Koen Vandendriessche (Belgium)

(Click here for pdf version of this article)

1. Introduction

Injuries of the Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CrCL) of the stifle are a common clinical finding in dogs of any breed, age and weight. CrCL injuries are consisting of partial tears and of complete rupture. The most common breed to have problems with cruciate ligaments is the Rottweiler. The two primary functions of the cranial cruciate ligament are to limit cranial translation of the tibia with respect to the femur, and to limit internal rotation of the tibia. When an excessive force is applied to the tibia, which causes forced internal rotation or cranial translation, the cranial cruciate ligament will rupture. Those forces could be applied in an acute and violent manner, like after a trauma causing an abrupt hyper extension of the knee and internal rotation of the foot leading to a partial or a complete ligament rupture. Such an event is most frequent in man and in active and sporting dogs, but in most dogs, the pathogenesis is different. In the dog, the rupture is caused by a continuous stress on the CrCL that damage bit by bit. The continuous stress on the damaged ligament leads to its partial and then complete rupture.

Partial tears of CrCL are associated to short-term and self- limiting acute lameness, most of the time evolving later in chronic grade 1 lameness, usually underestimated and leading to complete rupture after a variable time

CrCL complete rupture is clinically associated to acute grade 3 lameness and can be a consequence of a chronic tear or it can be associated to a recent acute trauma, usually consisting of stifle hyper extension and internal rotation, the same condition leading to traumatic partial tears when of less amount.

2. Diagnosis

The clinical signs associated with cranial cruciate ligament (CrCl) rupture vary depending upon the onset of the disease, the type of tear and the concurrent meniscal injury. Diagnosis is made from the history of lameness, physical examination, which usually reveals some degree of rear limb lameness, and with the help of radiographic examination. Gross enlargement of the joint due to thickening and fibrosis of the surrounding tissues, particularly of the medial aspect of the joint (medial buttress), is evident in chronic cases. Joint effusion is present in most cases and may be manifested by swelling of the joint with loss of palpable definition of the patellar tendon. Definitive clinical diagnosis is made by demonstrating a positive drawer sign and tibial compression test.

2.1. Drawer sign

Cranial drawer sign is a manipulation of the stifle created by the operator. The physician places his index finger on the patella and the thumb of the same hand on the fabella. With the other hand, the index finger is placed on the tibial tubercle and the thumb is placed on the head of the fibula. Cranial translation of the tibia with respect to the femur is attempted by operator force.

2.2. The tibial compression test (TCT)

The Tibial Compression Test (TCT) can be performed with the patient in standing position or in lateral recumbency. One operator’s hand is placed on the metatarsus, the other hand holds the stifle with the index finger positioned on tibial crest, the animal’s hock is flexed and in case of cranial cruciate rupture a cranial tibial displacement is detected. The test is performed with the leg in moderate extension and in flexion; interpretation is as for the cranial drawer sign.

2.3. Radiographic examination

On medio-lateral X-rays the first and unspecific signs of joint inflammation are represented by a positive fat pad sign and by a caudal displacement of popliteal fascia. The first osteoarthritic (OA) changes detectable in case of stifle pathology are represented by lipping of the distal patella and sclerosis of the trochlear groove. Moderate OA signs are lipping of the distal and proximal patella, osteophytes formation on the fabellae, sclerosis of the trochlear groove and sclerosis of the tibial plateau. When the OA signs become more severe, all the modifications described above will be evident, associated to osteophytes proliferation caudal to the tibial plateau and sclerosis in the digital extensor groove. Capsular thickening and joint distension may contribute to a false impression of stability.

3. Differential diagnosis

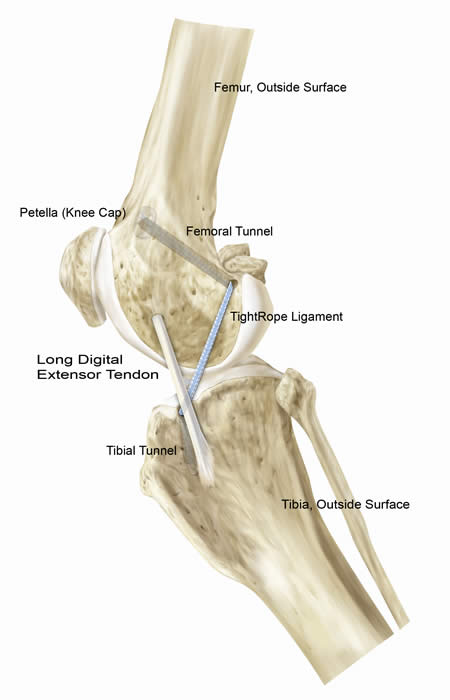

Differential diagnosis to cranial cruciate ligament injury include caudal cruciate ligament rupture, OCD of the femoral condyle, patellar luxation, collateral ligaments lesions, long digital extensor tendon avulsion and luxation, neoplasia.

4. Treatment

Here are different ways of treating a CrCL rupture. We like to stabilize the stifle joint with extracapsular stabilization, TPLO or TTA.

4.1. Extra capsular stabilization

Extracapsular stabilization of the cranial cruciate ligament deficient stifle is commonly performed to limit internal rotation, hyper extension and cranial translation of the tibia. Various modification of this procedure have been described.

The extracapsular technique relies on periarticular fibrosis for permanent stabilization of the joint.

Extracapsular suture is an effective technique in light, not active dogs, with a smal inclination slope. Numerous materials have been reported for extra capsular stabilization.

The use of absorbable suture materials provides not a prolonged restraint to abnormal movement.

Multifilament non absorbable suture materials have been used and provide prolonged restraint to abnormal movement, however, the use of these suture materials have been associated with a high incidence of postoperative infection and sinus tract formation.

Monofilament nylon leader is purported to have comparable mechanism strength to the multifilament non absorbable suture materials, but is less likely to harbor bacteria or become infected.

Fiber wire suture is constructed of a multi stranded long chain polyethylene core with a polyester braided racket that gives FiberWire strength, soft, feel and abrasion resistance. Suture breakage during knot tying is virtually eliminated.

Complication rate associated with this technique is about 17% and complications include: sliding off the suture from the fabella, displacement of the gastrocnemius sesamoid bone, tearing of the femoral-fabellar ligament or tibio-patellar tendon, too much entrapment of soft tissue beneath the suture or enlargement of the bone tunnel, thus resulting in persistent instability, neurologic deficits, surgical site infection, incisional complication, meniscal late damage and implant -related complications

4.2 TPLO (Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy) versus TTA (Tibial Tuberosity Advancement)

We will discuss those two techniques together so that you can see better the differences between both techniques.

During the past decade, complete or partial rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament in dogs has become one of the preeminent topics of interest in small animal orthopedic surgery because of both the high incidence of the problem and the clinical success of treating it. While the majority of cases are still treated by other methods tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) is, by a broad consensus, a state-of-the-art repair method. A newer technique, called tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA), which became established for clinical use in early 2004 is now also a worldwide used technique. With the TTA technique can we achieve that the total joint force runs nearly parallel to the patellar ligament by moving the tibial tuberosity cranially.

After cranial advancement of the tibial insertion of the patellar ligament, the ligament is perpendicular to the tibial plateau, there is no shear component of the total joint force of weight bearing and the cruciate ligament is no longer loaded.

TPLO

Advantages of TPLO

The procedure can be performed in dogs of any size, from 1 to 100 kg., with whatever tibial slope. Tibial slope correction is precise and accurate. With TPLO, it is possible to correct common malalignment problems, often correlated to cruciate ligament injuries, like tibial varus/valgus and internal/external tibial torsion. With proper surgical technique, complication rate is low and the effiency of this procedure is confirmed by over 60 thousand dogs treated in the world.

Disadvantages of TPLO

Because of increased flexion of the stifle achieved by tibial plateau leveling, when the dog is sitting and rising the caudal horn of the medial meniscus is pressed by the femoral condyle; therefore, Slocum recommended to perform the meniscal release to free the caudal horn of medial meniscus. The lost integrity of the meniscus is detrimental for the joint function. Some increase in osteoarthritis progression has been associated to meniscal release. TPLO decrease joint flexion in the same amount of the tibial slope rotation.

TTA

Advantages of TTA

TTA’s main advantage is the preservation of meniscal integrity. Because the stifle becomes stable even in maximum flexion, when the dog is sitting and rising, there should not be no need to perform meniscal release. In dogs with marrow tibia TTA restore a more balanced anatomical tibial morphology increasing the lever arm inside the joint and thus decreasing the forces on the joint surfaces.

The procedure is less invasive than TPLO because the osteotomy is not crossing the loading bone column, and the recovery time is faster. In partial cruciate ligament ruptures the TTA prevents further ligament sprain. The implants are in titanium, being the most well tolerated material by the body. The technical difficulty is similar to the one required for TPLO, but the surgical time is little less.

Disadvantages of TTA

The main disadvantages of TTA is the inability to correct excessive tibial slopes (>29°), the impossibility to correct with this procedure any malalignment. A practical disadvantage of this procedure is the complexity and the cost of the implants (all in titanium), with several sizes and special screws and the need of a always available complete stock.

5. Aftercare

Whatever technique is used, the aftercare is more important than the surgery itself.

For eight to twelve weeks following surgery, a strict confinement regime is required with three important principles:

1. Your pet can be inside, on carpeted surfaces, under your direct supervision. It can wander around the room at a slow pace as long as it is not constant. Running, jumping, bounding, playing, etc., are not allowed.

2. Your pet must be on a leash at all times when outside for airing and going to the bathroom. If the animal has to cross slick floors or uneven ground, you need to use a “belly-band” in case it slips or stumbles. The “belly-band” is not used for support but rather as a safety net to protect your pet.

3. Your pet is not allowed to be off leash when outside or to go for an actual walk.

When not under your direct supervision, your pet is to be confined in an airline kennel or equivalent.

General Information:

– Playing with other animals is not allowed during confinement. If there are other pets in your household, you will need to keep them separated.

– During confinement, your pet’s food intake needs to be reduced to help prevent weight gain. Most dogs will maintain their current weight if their food intake is cut in half. Water consumption should remain normal.

– The first two weeks following surgery you will need to monitor your pet’s incisions. Licking or chewing can cause infection or sutures to loosen. If you notice that your pet has started licking, you will need to take steps to discourage it from doing so. It takes a minimum of six to eight weeks for bones to heal.

– One of the most difficult aspects of confinement is that the animals will frequently feel better long before they are healed. At this point, your pet will start being more careless of the operated limb and is then more likely to be overactive and injure itself. Until the bone is healed, you must adhere strictly to the confinement guidelines and not allow your pet to do more.

– If your pet is jumping, or bouncing, in its confined area, it is being too active. Tranquilizers may be required to help alleviate your pet’s anxiety or control its activity.

– If, at any time during your pet’s recovery and healing, it does anything that causes it to cry out or give a sharp yelp, contact your veterinarian.

– Following surgery, your pet should always maintain at its current level of function, or improve. If, at any time during your pet’s recovery and healing, it has a set back, or decrease in function, contact your veterinarian.

– It is imperative that you inform your veterinarian at once if your pet does something that is potentially harmful to the surgery. If something has occurred which jeopardizes the outcome of surgery, it is usually less difficult to correct if it is caught right away, which leads to a better outcome for your pet.

– If your pet is too active during its confinement, it may injure itself or slow healing which increases the amount of time your pet must be confined.

– Follow up appointments are usually needed two weeks post-operatively to monitor incisions and healing. At eight weeks post-operatively radiographs are taken at which time your pet is started on a regulated activity regime. A final appointment at four months post-operatively is needed for additional radiographs and final instructions before returning your pet to normal activity.